Tuesday, July 31, 2007

Microsoft Vista

I also have the new office. The most annoying thing about that is the default in Word is Calibri size 11. What happened to Times New Roman 12? I’m learning where everything is in Office 2007, and I think I like it better, but just need a little more practice with it.

All in all I like Vista better than XP when it is fully functional. But the daily crashing of the internet, occasional crashing of the computer, and ridiculously long boot up and shut down times makes it not worth it to upgrade. When Microsoft can afford to hire programmers to make the internet work on their own software, then I think you should consider the upgrade.

Monday, July 30, 2007

The Book Revue: The Politics of American Religious Identy, by Kathleen Flake

Since it's been a few weeks since I finished it, I owe an installment to the Book Revue. Kathleen Flake's The Politics of American Religious Identity: The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot, Mormon Apostle is worth a read for anyone who has interest in Mormon history, the decline of the Protestant political establishment, or church-state issues in the U.S.

What you have to know about Kathleen Flake is that she is incredibly smart. She possesses not only a historian's ability to survey huge amounts of material, but also the analytical gift of distilling a clean, precise, conclusion. She combines these scholarly gifts with the faith and experience of living inside the Mormon church. As a result, her writing is simultaneously challenging and uplifting to faithful and outsiders alike. I was first introduced to her through her 1992 Essay "Supping with the Lord: a Liturgical Theology of the LDS Sacrament." Her thoughtful analysis of one of the core ordinances of Mormonism takes a look at the similarities and differences between the two prayers, and between this ordinance as compared to other Eucharistic rituals. The combination of close textual analysis and thoughtful faith is rare in a world where writing about religion too often devolves into criticisms or apologetics.

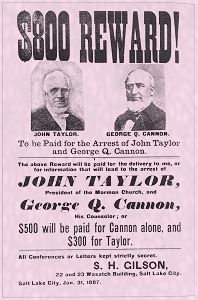

This book is no different. In it, Flake examines how the church went from being an isolated polygamous, theocratic sect holed up in the Rocky Mountains to being the integrated conservative, uber-American, ultra-patriotic, nuclear family centered church that it is today. The traditional narrative accepted in Mormon studies placed the crux of that transition at the moment of President Woodruff's manifesto.

But one major problem with the traditional narrative is that the manifesto was in many ways a non-event. The church was locked in a fight with the republican federal government, both sides committed to win, and the situation changed very little immediately after the manifesto. Though we take it seriously today, it wasn't always regarded as so binding. While "the church" didn't sanction or solemnize plural marriages after the manifesto, several apostles did, with knowledge (and some have argued, implicit approval) of the President of the Church. While the excerpts appended to the manifesto in the current printing of the scriptures uses the language of revelation and vision, The language of the manifesto itself presents itself not as binding, but as "advice," and grounds itself not in revelation, but in the fact that plural marriages are "against the law of the land." (Greg Smith's article gives a more comprehensive view of post-manifesto polygamy). There were enough Mormons still continuing to marry polygamously that President Joseph F. Smith issued what is sometimes called the "Second Manifesto" in 1904. The major difference from the 1890 manifesto is that it specifically threatened excommunication to solemnizers of plural marriages. The fact is that the 1890 manifesto was not the colossal moment that some historians have made it out to be.

Flake's book asserts that it was Reed Smoot's election to the Senate that precipitated the change associated with the Second Manifesto. She details how the Senate at the time was dominated by a powerful but weakening protestant establishment; not an organization, but the informal cooperation of individuals and groups with a shared understanding and agenda. The Smoot hearings were the clash between the (largely) republican protestant movement and the Mormon church. Bent on destroying the remaining "twin relic of barbarism," the republican party was not going to back down. However, this time the fight was political; it was fought in committee rooms rather than on the battlefield and in the courtroom and the jailhouse. The result was compromise and accommodation on both sides.

Flake's book asserts that it was Reed Smoot's election to the Senate that precipitated the change associated with the Second Manifesto. She details how the Senate at the time was dominated by a powerful but weakening protestant establishment; not an organization, but the informal cooperation of individuals and groups with a shared understanding and agenda. The Smoot hearings were the clash between the (largely) republican protestant movement and the Mormon church. Bent on destroying the remaining "twin relic of barbarism," the republican party was not going to back down. However, this time the fight was political; it was fought in committee rooms rather than on the battlefield and in the courtroom and the jailhouse. The result was compromise and accommodation on both sides.But most surprising to me, was the portrait that Flake paints of Joseph F. Smith. I came away from this book viewing President Smith not just as a prophet, but as a brilliant strategist who was forced to act as an intermediary between the hostile federal government and his own people. Flake explores how at the same time he committed the church to the eradication of polygamy, President Smith also began to place renewed emphasis on the First Vision to ensure that the church would not lose its uniqueness. With its commonwealth assimilated, its independence a thing of the past, and its most distinctive practices abolished, President Smith turned the church to its distinctive doctrines.

And one need not worry that Flake's book is damaging to Mormon faith. While I wouldn't make it part of the Sunday School curriculum, it tells a faithful, honest story. It must be remembered that Flake is a Latter-day Saint, which makes it clear that while the issues raised by this period of church history may challenge the understanding, they do not have to destroy or weaken faith. Recently, even Elder Dallin H. Oaks of the Quorum of the Twelve spoke favorably of this book, calling it "the best thing ever written on [the church's transition from isolation to assimilation]." On Joseph F. Smith's role in the transition, Elder Oaks says that Flake "wrote about that so movingly, and I’d never thought of it. That was something that was new to me, but it rang true." (Read the whole interview here.)

Bottom line: The Politics of American Religious Identity: The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot, Mormon Apostle is a great, well-researched, and thoughtful book. It ought to be required reading for anyone interested in studying Mormon history at the turn of the century.

Euterpeos: They Might Be Giants' The Else

They Might Be Giants has been evading genre definitions since 1982, only barely snagging itself in the catch-all nets of indie and alternative rock. While their music can be considered both indie and alternative, those labels don’t really do justice to the diversity of John and John’s work. Analysis of 25 years of music reveals influences from 60s rock & roll, 80s electronic pop, 90s alternative, folk, jazz, blues, show tunes, punk, ska, et cetera. You can’t really pin a sound or a label on the music of They Might Be Giants. The same statement applies to their new album: The Else.

If I were going to try to call The Else something, I’d call it electropunk. The plurality of the tracks (“I’m Impressed,” “Take Out the Trash,” “Climbing the Walls,” “The Cap’m,” “The Shadow Government,” “Feign Amnesia”) seem to call on that genre as influence, though admittedly some are more electro and others more punk. Two of the tracks (“Careful What You Pack,” “Withered Hope”) have an eerie, Sufjan Stevens-esque sound. The rest (“Upside Down Frown,” “With the Dark,” “The Bee of the Bird of the Moth,” “Contrecoup,” “The Mesopotamians”) stubbornly refuse to be lumped in with any of the others.

Electropunk is a fairly new and different sound for TMBG. Adopting it for their latest album shows the band’s continuing ability to adapt itself and successfully innovate. The Sufjan Stevens influence demonstrates TMBG’s ability to stay current with musical trends while maintaining a style of their own.

The Else also succeeds in demonstrating TMBG’s other quality that has helped the band’s staying power: the ability to compose songs on subjects that nobody else would consider musical. “The Shadow Government” talks about a corrupt municipality; the lyrical voice yearns for an overthrow that will allow him to run his meth lab without local, invasive surveillance tracking him. “The Bee of the Bird of the Moth” describes the actions of the hummingbird moth, which acts “like a bird that thinks it’s a bee.” “Contrecoup” advocates the use of phrenology to examine a concussion. “With the Dark” was hard to understand at first, but after watching the music video of it on YouTube, I determined that the song is about a girl and her love for a giant squid, whom she abandoned to take over the world with her little friend that she spontaneously generated.

“The Mesopotamians,” in my opinion, deserves special mention. When I first saw this track listing, I assumed that it would be one of the band’s quasi-educational songs, in the same vein as “Why Does the Sun Shine?” or “James K. Polk.” The song, whose tune and composition recall something from The Turtles’ greatest hits, is actually about a band named The Mesopotamians. The members of the band are Sargon, Hammurabi, Ashurbanipal, and Gilgamesh. No one’s ever seen them, and no one’s ever heard of their band, but they drive around in an Econoline van and scratch their lyrics down in the clay in case someone one day gives a damn about them. Ingenious. And by ingenious, I mean who in the world would have thought to write such a song?

Overall, The Else is an enjoyable album. It’s exactly what you would expect from TMBG (quirky, original lyrics and music), augmented by the band’s continuing ability to reinvent their sound and adapt to modern musical tastes. And they do it all without selling out. Bravo John, John.

Overall, The Else is an enjoyable album. It’s exactly what you would expect from TMBG (quirky, original lyrics and music), augmented by the band’s continuing ability to reinvent their sound and adapt to modern musical tastes. And they do it all without selling out. Bravo John, John.

Thursday, July 26, 2007

Cinematographicus: The Illusionist (2006)

Every once in a while a movie comes out that I want to see, but it doesn't look exciting enough to pay full price for it, so I wait until I have an open afternoon and I go to a matinee showing. Then there are those movies that catch my curiosity, but not to the point where I want to spend even matinee prices to see it when I could use the six bucks toward something more fulfilling. That's when I wait until the movie is released in the dollar theater, accepting the fact that I'll have to deal with crowds of high school kids, extra-sticky floors, mediocre sound, and a few reels of film stock that look like they've been unraveled and dragged behind a truck for fifty miles. Sometimes, though, a movie barely catches my attention, and I hear one or two people talking about it, so after six or seven months of its original release I finally work up a spark of a desire to see it. That's where Redbox comes in, and that's the setup for my viewing of "The Illusionist," last year's response to Christopher Nolan's ingenious "The Prestige." (Yes, the latter was released second, but I believe it went into pre-production first.)

However, to be fair, I will refrain from making comparisons between the two, though the "coincidence" in the timing of their releases is uncanny. My comments directed to the film are as a standalone work. That being said, I continue:

BOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO!!!!!

What a waste of great performing talent. Paul Giamatti steals the show simply by further displaying his versatile abilities, yet his character is nothing more than the ignorant sheriff. Edward Norton has earned my respect as an actor, yet as a masculine hero in this movie he comes off more as a weenie child. Rufus Sewell, who plays the haughty villain in every movie you'll ever see him in (except for the aptly-titled "Amazing Grace," where he somewhat suspiciously plays a morally-upstanding inspiration behind the abolition of slavery in England), follows tradition here with an antagonist so shallow that his every thought and action are predictable: suave facade, irritation at protagonist, revelation of evil plans, furious reaction at others' happiness, hamartia demonstrated in the heat of passion, suave cover up, nervous reaction to unexpected evidence, insane downfall. His character might as well have been modeled after Dean Jones' character in "Beethoven" (1992). Finally, Jessica Biel wasn't looking nearly as hot as she could have.

I kept looking at the time, wondering how far I was going to get into the movie before deciding that I was finally being entertained. The whole movie felt like a setup rather than exposition of an actual plot: a childhood forbidden love is reintroduced to two now-adults, who must find a way to be together until they encounter a dire obstacle. We dwell so much on one or two pieces of what could have been a very grandiose puzzle, but are cheated with an attempt at a clever twist at the end that anyone can see coming from miles away -- which says something for the town sheriff, who takes no part in proactive thought until 90 minutes after we've already solved the riddle. I hate feeling smarter than the supposed experts in the story, especially when I'm no detective. That means that the writers created unintelligent characters.

All of this means that the slow pacing of the film makes you glad it's under two hours' length since you aren't really being taken anywhere worthwhile.

It's worth a Redbox rental to satisfy any lingering curiosity you may have after reading a very belated review. However, might I make a suggestion? With the one dollar you would have otherwise used to check this disappointment out, go see "The Prestige" instead -- even if this will be the fifth time you see it.

Tuesday, July 24, 2007

Happy Pioneer Day: They of the last wagon.

I have a love-hate relationship with this holiday. I love my ancestors who are remembered on this day, and the sacrifice that they went through to preserve the church. I hate the fact that sometimes it is an excuse to perpetuate the cultural aristocracy that we sometimes see whereby those who descend from the famous families in church history are seemingly more important than rank-and-file members.

I know, I know, there's also lots of talk about modern pioneers. But sometimes, the modern pioneer thing sounds to me more like an apologetic afterthought than sincere praise. It's not that I'm bitter or jealous, either; I have a pretty rich church history pedigree myself. I just don't like the aristocratic tendencies it creates. It seems at odds with the democratic and egalitarian attitudes the gospel seems to espouse. God could raise up children of Abraham from inanimate rocks if he wanted to.

That's why I love this talk. Given by J. Reuben Clark in 1947, it should be read every July 24th.

Friday, July 20, 2007

Civitate Dei

As I shuttle back and forth between the farmland of western Minnesota and the concrete island of Minneapolis, I've been thinking about the difference between the city and the country. Specifically, what role does the city/country dichotomy play in the gospel?

As I shuttle back and forth between the farmland of western Minnesota and the concrete island of Minneapolis, I've been thinking about the difference between the city and the country. Specifically, what role does the city/country dichotomy play in the gospel?Christianity has always seemed to hold some kind of pastoral aesthetic as an ideal. David's cry that "The Lord is my shepherd" resonates with Christians still. This pastoral theme begins almost immediately after the fall. Abel, the first martyr, was a keeper of flocks. Abraham and the patriarchs were also keepers of flocks. The Law of Moses, with its myriad of animal sacrifice requirements was a law for shepherds. Moses himself receives his prophetic call after forsaking Egypt and taking on the life of a herdsman with Jethro.

Then there's also this intertwined idea of the wilderness (and mountains in particular) as sacred space. Think of Eden, Ararat, Sinai, Canaan and even Israel's travels. The prophets are always calling the faithful out of the civilization of Egypt to the ascetic purification of the wilderness. It continues in the New Testament, where Jesus' birth is first announced to Shephards. John the Baptist is descried "as one crying in the wilderness." Jesus preaches his greatest sermon on a mountain. Even Calvary is outside the city. Eden was a garden, and Gethsemane, even though it was inside the city, was a garden, a sacred green space.

This idea is even stronger in Mormonism where the Book of Mormon explicitly says that the Lord "leadeth the righteous away into precious lands." Think of the Jaredites, the Mulekites, Lehi and family, and even Nephi doing it again to get away from Laman and Lemuel. Both Nephi and Jared's brother have spiritual experience on mountains, separated from civilization. Both

take their followers out of the city and into the wilderness. The same exodus motif is re-enacted in LDS history as well, with the saints leaving one place after another. Not just the trek to Salt Lake, but the departures from New York, from Harmony, from Kirtland, from Missouri, and from Nauvoo all replay the same pattern.

take their followers out of the city and into the wilderness. The same exodus motif is re-enacted in LDS history as well, with the saints leaving one place after another. Not just the trek to Salt Lake, but the departures from New York, from Harmony, from Kirtland, from Missouri, and from Nauvoo all replay the same pattern.Then, in addition to the pastoral ideal and the sacred wilderness/exodus motif, there is the recurring image of evil represented by a city or a building. Babel is the earliest example, then you have Sodom and Gomorrah and Babylon. In the New Testament Babylon is resurrected as a type and applied to hedonistic and oppressive Rome. Jerusalem, though it is the Holy City, is depicted a the nest of Herod's corrupt regime and the Pharisees' religious oppression. Again, the Book of Mormon follows the same pattern, where in Lehi's vision goodness is represented as a tree and evil, "the pride of the world" is a building, not just a humble dwelling, but a "great and spacious" building full of "all manner" of people whose "manner of dress [is] very fine." It is a cosmopolitan place. Then you have the voice of Christ in the darkness declaiming the destruction of wicked cities. The Doctrine and Covenants reinforces the Babylon motif by using Babylon as a type, but also by issuing warnings to specific American cities.

So there are three interweaving themes going on: the pastoral ideal, the wilderness motif, and the Babylon motif. These together create a kind of preference for rural life and a distrust toward the city. Even Augustine's city of god was not a physical place, but a transcendant community of believers.

But even though the anti-urban mood does seem to predominate, there is another side to the story. Jerusalem is kind of ambivalent. On the one hand, it is the holy city; on the other, it is still corrupt. But there is Enoch's city, even older than Jerusalem. Zion stands out as a foil to the Babylon motif. In the advance of metropolitan Babylon, the righteous always seem to flee. The exodus motif does this. John's apocalypse gives us the image of the church, symbolised as a woman, fleeing into the wilderness. But Zion is different.

In the case of Zion, the righteous did flee, but not into the wilderness. Instead, the saying "Zion has fled" meant that the city itself was taken up into heaven as a city proper, not as a nomadic group of strangers and pilgrims. Zion seems to be the only example of an uncorrupted holy metropolis. The righteous didn't leave the city, they took it with them.

Part of the genius of the restoration is that it tapped into this almost-forgotten Zion myth (myth in the positive sense). Early Mormonism was a metropolitan, even cosmopolitan endeavor. Today, we lionize the pioneers as pilgrims and idealize their peregrinations. But no matter how much we see the exodus parallels in the wesward trek, the Pioneers were different from the nomads of the Old Testament because they didn't go to the wilderness to get away from the city, they went there to build a city. Joseph Smith was a city planner and builder. Kirtland and most especially Nauvoo demonstrate his metropolitan tendencies and abilities. The Mormons' Missouri and Illinois antagonists were not the cosmopolitan sinners of Sodom and Gomorrah, they were the unwashed "border ruffians" of the American frontier. Nauvoo was bigger than Chicago, it was not a quanit town, it was a city. Mostly easterners and immigrants from the great cities of Europe, the Mormons were the cosmopolitans.

And Mormonism, because of the missionary program, has a tradition of holy and sacred events taking place in cities. In the larger Christian tradition, missionary work is most often taken to far-off, benighted lands, the far east and Asia. Though this is starting to change as Europe gets less religious, the idea was that the "Christian" nations didn't need missionaries. Mormonism (along with the Witnesses and a few other small sects) is unique in that it sends its missionaries to America's great cities. So when Joseph Smith sends Brigham Young and Heber Kimball to England, they go straight to the heart of the industrial center of England, Manchester. Here they wrestle with Satan and baptize hundreds. Sacred history is created, in the city.

So is the city a place to celebrate, or a place to flee out of? Are all cities evil if they are not Zion?

I'm reminded of Ninevah. That great city took three days to walk across. Jonah is interesting because he is in many ways the anti-prophet. The Book of Jonah flips things around. He runs away from his prophetic call, he preaches only grudgingly, and then he's upset when the people repent. The Ninevites don't play their role in the expected way because they actually repent. The whole prophet narrative is backwards. The topsy-turvy world of the Book of Jonah also flips around the traditional city/wilderness dichotomy as well. Near the end of the book we find the prophet outside of the city, in the wilderness, being childish, petty, ethnocentric and melodramatic, while the city-zens are inside the city, repenting in sackloth and ashes. The sacred space is inside the city. The wilderness is not the sacred space.

I'm reminded of Ninevah. That great city took three days to walk across. Jonah is interesting because he is in many ways the anti-prophet. The Book of Jonah flips things around. He runs away from his prophetic call, he preaches only grudgingly, and then he's upset when the people repent. The Ninevites don't play their role in the expected way because they actually repent. The whole prophet narrative is backwards. The topsy-turvy world of the Book of Jonah also flips around the traditional city/wilderness dichotomy as well. Near the end of the book we find the prophet outside of the city, in the wilderness, being childish, petty, ethnocentric and melodramatic, while the city-zens are inside the city, repenting in sackloth and ashes. The sacred space is inside the city. The wilderness is not the sacred space.So is Ninevah just anomoly? What attitude do our traditions and sacred texts take toward the city? Is the city only capable of Zion when it's also a theocracy, or will our secular cities be redeemed like Ninevah?

Tuesday, July 17, 2007

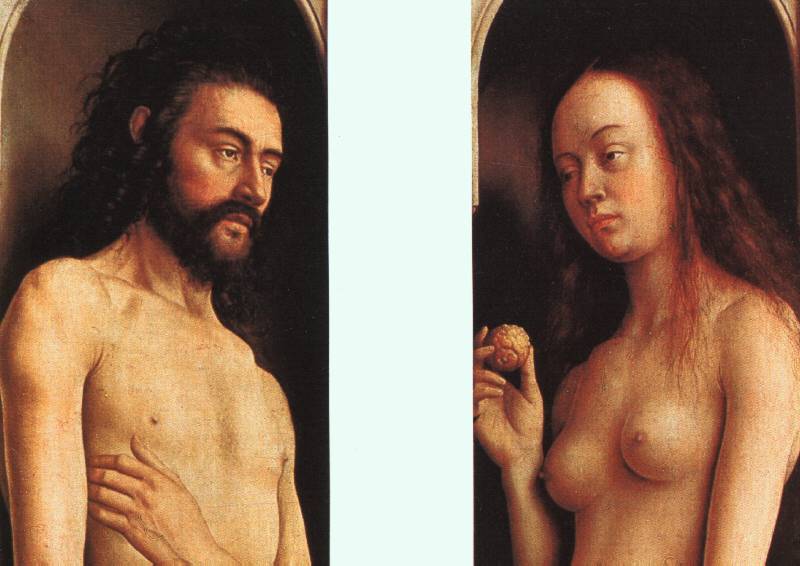

Playing Adam: Naming the cat

Recently, some friends of ours got a cat. Actually, that's not quite accurate. They adopted a domesticated Bengal from a shelter. A Bengal is a cross-breed between domesticated Asian leopards and ordinary housecats. She looks a lot like a cat, but she's longer, shorter, has silkier fur, with spots, and instead of walking like a normal cat she kind of slinks around all low to the ground. And she has much bigger claws. I'm not a cat person, but I thought she was pretty cool.

But they haven't yet named her. They asked for help. I had a few ideas, but nothing I felt strongly about. Here are a few:

1. Sophia: I just think it would be cool to name a cat after the goddess of wisdom.

2. Minerva: ditto.

3. Sphinx: what's her secret?

4. Anubis: I think this is an awesome name for a cat, but it kind of has to be a black cat, and a male.

5. General Tsao: awesome name, but I think its fits a male cat a little better.

6. Cleopatra: I like it, but isn't it a little commonplace as a cat name?

7. Grandma Moses: I like the idea of naming pets after historical figures. My property prof last year had a dog named William the Conqueror. I'd like to name a dog Lord Byron. Pushkin is also a god name for a dog, but it has to be a huskie or malamute. Plus, if they called her Grandma Moses, she could be G-Mo for short.

8. Boudica: always a good choice.

9. Pantera: this has the advantage of doubling as a cat-like name and a metal band name.

10. Nefretiri: I like it.

Any other suggestions? Which of these is best?

Monday, July 16, 2007

It is not good that man should be alone.

I'm a little over halfway through a summer of intermittent separation from my spouse.

I took a job this summer doing outreach and client intake with migrant farmworkers as a paralegal with Migrant Legal Services. It's a great job because it carries a more real sense of fulfillment than some jobs, because it gives me a lot of concrete experience working directly with clients, with opposing parties, and with administrative agencies, and because I get to speak Spanish.

But the trade-off is that I am required to be away from home about half the week. At the beginning, I would leave Monday morning, work in three different towns, and get back Thursday sometime between 6 and 11:30 depending on what was scheduled. We kept on telling ourselves that since I'm only gone three nights/week, I'm still home the majority of the time. But I think we may have engaged in a bit of self-deception. The reality is that I was still gone more than half the days of the week and more than a third of the the nights of the week. Since Mrs. JKC is also pregnant, and since we found out about the time I began this job, the separation seems acuter.

My schedule has since altered and I'm now coming back a day earlier, which is nice. But it's still hard to be away.

I know that we have it better than many others, and maybe I shouldn't be complaining. But it's odd how sad I've felt the past two weeks as my endurance has worn ragged. I remember feeling this way a little bit back in my previous life as a single person at BYU. Lonely. Eating horrendous amounts of nachos for dinner, commiserating with similarly single roommates, fantasizing about relationships, complaining about bad dates, etc.

But that was different. Back then it was easier to revel in it. I could put on my headphones and roam the rainy streets of London at night to the melancholy repetition of "Only in Dreams," and not feel too pathetic because it was kind of romantic. Maybe spending too much time in a classroom with Nick Mason and having a few of those tortured artist type friends allowed me to see myself not just as sad, but as gloriously lonely. I was like "yeah, I totally get The Cure." Because I know how cruel loneliness can be. Not that I was an emo kid or anything. But sometimes, it was fun to wallow in the cliched mire of self-indulgent loneliness.

But now I miss someone I actually do have, not some ephemeral fantasy of my own creation. And the fact that I'll see her again in only a few scores of hours kind of makes me feel more pathetic for not having the guts to stick it out. We were apart for two months while engaged and I was able to play the tortured separated lover with some kind of panache. But now, if I start to feel the urge to revel in it, then I feel this counter-urge that tells me I'm being juvenile and stupid, that I should put away such childish things.

Why is that? Have two years matured me so much that I can't identify with all those musical laments anymore? Has marriage matured me? I'm still the same dude, I think. Did two semesters of law school purge that sentimentality out of me? Or should I just go ahead and indulge?

I just don't want to go away anymore.

Tuesday, July 10, 2007

Eyes vs. Ears

Can you read an audiobook?

Nobody would ever say "I listened to that book" if he were talking about a bundle of printed sheets, but it is common to hear people claiming to have read a book when the "reading" was done with the ears, not the eyes. A literalist would call such declarations either mistaken or disingenuous. Is she wrong?

On the one hand, why should it matter how the words get into your head if they do get there? If you're digesting the message, why does the form matter?

On the other hand, though, a modern proverb tells us that the medium is the message. While I'm not sure that that is always true, it is true that the delivery of the message changes, or at least affects, the message. So if you read an audiobook, you are probably not having the same experience as the average reader of the book. The message is changed, even if slightly. But how far can this logic work? If I read a translation of Les Miserables have I actually read Les Miserables? The medium is changed, so have I actually read the book, or have I only read an adaptation of it?

But even if the medium changes the message, it isn't clear that it's a bad change. Maybe some books are better heard than read. Some things will be easier to see on a page, others will be easier to hear. Rhythms, sarcastic nuances, inflected subtlties are better heard than read. Structural patterns are usually better when you can flip back to examine them. On the whole, I think the sentence is better heard, but the paragraph is better read.

Which is a conundrum. Which is a better way to experience a text?

I guess for me it depends on the genre. A lyrical, poetic work narrative-driven work focuses on images, and is better heard, where the imagination can give them the breath of life. But an academic, logic driven work focuses on abstractions, and is better read, where the relationships can be concretely seen.

Or am I wrong? Should books be read, plays be seen, and speeches heard, or does it not matter?

Monday, July 9, 2007

The Book Revue: a dystopian reader

I was first introduced to Margaret Atwood by my wife, who is the proud owner of a paperback copy of every Atwood novel. However, it wasn't until I my senior English seminar on Utopian and Dystopian literature that I read one of her books, The Handmaid's Tale. In that same course, we also read The Republic, Utopia, Gulliver's Travels, Herland, We, 1984, Brave New World, The Dispossessed, and I'm probably not remembering a few.

So what follows is my attempt at a few recommendations of dystopic literature:

1. 1984 is kind of like the granddaddy of the genre. It isn't the oldest or the biggest or the most complex, but it is probably the most read and the most influential. It is the most political, for sure, and perhaps the most enduringly relevant.

2. The Time Machine is not the most elegantly written piece of fiction out there, but it remains one of my favorites. It was truly inventive for Wells to take social stratification to its most frightening Darwinian conclusion.

3. Brave New World is a well-written work by a truly crazy man. It really makes you think. I wonder, though, how many of the politicos who cite it in their fear-mongering about stem cells have actually read it.

4. The Road is a recent novel by a man who customarily writes stories about cowboys and sunsets and dangerous mexican jails and bleak desolate country and what it means to be a man. It is a post-apocalyptic account of a man and his son (Abraham/Isaac and God/Christ comparisons are inevitable) trying to survive. It is probably the most gorgeous on my list in its use of language. The most poetic, the most lyrical. I actually cried.

5. Oryx and Crake is, as noted above, fantastic. I think it's better than Handmaid's Tale. At least, the fact that it is less in-your-face feminist makes it seem a bit more universal, and it explores the themes common to the genre more deeply than Handmaid's Tale.

6. A few selections of the Book of Mormon (The Book of Fourth Nephi and The Book of Ether), I think qualify as dystopian writing.

7. Some helpful background: it is almost impossible to read some of these pieces without an understanding of a few biblical stories: Eden, and Abraham and Issac are probably the two most critical. Sir Thomas More's Utopia is also helpful, as is The Republic, as well as some cursory knowledge of Marxism and Utilitarianism. Knowing Shakespeare makes everything better, and these books are no exception.

Any other thoughts? Have I missed any? Any that don't belong here?

Tuesday, July 3, 2007

Independence Day: ¡Viva la revolución!

In Church on Sunday we sang the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” to open the meeting. The “Battle Hymn” has a kind of earnest Victorian-esque zeal worthy of Shaw’s Major Barbara. Until recently, I always thought that this rousing Christian hymn predated the uncouth and irreligious “John Brown’s body lies a-moulderin’ in the grave” and that the good Christian version was the original.

But I was wrong. “John Brown’s Body” was a folk song, and like all good folk songs, has no identifiable author, but is the anonymous collective product of the great mass of un-elite humanity. It originated during the civil war among union troops who would sing it to lift their spirits and to convince themselves that they were fighting for the end of slavery.

Later, the daughter of a Lieutenant Colonel in the Continental Army Christianized “John Brown’s Body” by rewriting it, removing those pesky, possibly idolatrous references to Osawatomie Brown and replacing the marching of Brown’s soul with the marching of God’s truth. But even with these variations on the original theme, the origins of Howe’s “Battle Hymn of the Republic” are anchored squarely in the Civil War and specifically, with the call to end slavery. When Howe admonishes “as he died to make men holy, let us die to make men free,” it isn’t just some abstract kind of freedom she is talking about, but real physical, freedom. This makes the hymn more visceral to me, and therefore, more powerful.

And it seems, to quote another Civil War text “altogether fitting and proper” that I should commemorate Independence Day by remembering not just Lexington and Concord, Valley Forge, and Yorktown, but also Harper’s Ferry, Antietum and Gettysburg. 1776 was the birth of American freedom, but Lincoln hoped the Civil War would bring a “new birth of freedom.”

His hope was prophetic. It is not hyperbole to call the Civil War the second birth of this country. The country we live in now owes as much to the Civil War and the subsequent reconstruction as it does to the Boston Tea Party and the Constitutional Convention. The Civil War did two things: it created the legal system that defines questions of individual rights in this county, and it unified a loose group of states into one solid nation. Brown vs. Board of Education, arguably the most impactful court decision of the century, was based in the civil war amendments. Virtually any Supreme Court decision dealing with individual rights goes through the 14th Amendment. Before the Civil War, history books said that the United States are or were. Now, we say that the United States is or was. Ungrammatical, but significant. The revolution made us free, but the Civil War made us a nation.

But isn’t just the impact of the Civil War, it is also the substance of what that war was about that makes it meaningful to our independence. The second paragraph of the founding document of independence codifies what was later called our creed, that all are equal. If equality is the creed our independence, then slavery was our great national blasphemy. The causes of the Civil War are complex. It is too simplistic to just say that the Civil War was caused by slavery. But even if the war wasn’t about slavery when it started, it soon became a war about slavery. It was about slavery to the troops who sang “John Brown’s Body” and it was certainly about slavery to the emancipated African-Americans.

But isn’t just the impact of the Civil War, it is also the substance of what that war was about that makes it meaningful to our independence. The second paragraph of the founding document of independence codifies what was later called our creed, that all are equal. If equality is the creed our independence, then slavery was our great national blasphemy. The causes of the Civil War are complex. It is too simplistic to just say that the Civil War was caused by slavery. But even if the war wasn’t about slavery when it started, it soon became a war about slavery. It was about slavery to the troops who sang “John Brown’s Body” and it was certainly about slavery to the emancipated African-Americans.

And it was about slavery to the confederate leadership itself. It is often said that the confederacy was only concerned about states rights. But the right the secessionist states were asserting was the right to keep human beings as property because of race. Consider confederate Vice President Alexander Stevenson’s assessment of Jefferson's Declaration of Independence:

His ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. This was an error ... Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.

The secessionists were not just conservatives who failed to progress beyond slavery with the rest of the country; they were reactionaries who had actually repudiated the first of the self-evident truths that were articulated to justify American independence. This position essentially killed the revolution in the secessionist states. Its defeat, then, is appropriately called a “new birth of freedom.”

So tomorrow I will not just celebrate the war that won our political independence from a foppish monarchy. I will celebrate the war that won our economic independence from a racist ideology anathema our national creed. Together with the birth of freedom, I will celebrate the new birth of freedom that caused us to take that creed seriously enough to make it a part of our constitution. For those who, like me, believe that the principles of the Revolution are God's truth, and that they apply to all people, not just to America, Howe's prophetic phrase is hopeful and optimistic. Racism isn’t dead yet, but “His truth is marching on.”